Jim Shane

New Technology Yielding New Migration Data for American Kestrels

In one of the largest U.S. states, our partners at the University of North Texas (UNT) are studying one of the smallest raptors: the American Kestrel. This winter marked the ninth season of data collection for the UNT team, whose campus in Denton County, Texas, is smack in the middle of one of the largest concentrations of wintering kestrels in the world. By tagging kestrels in the area and tracking their movements both during the winter and beyond, the team hopes to gain insight into the stressors affecting the species.

“This year, we caught and marked 69 American Kestrels and deployed 25 radio transmitters,” reports graduate student and project field lead Brooke Prater. These transmitters—in part purchased by The Peregrine Fund—enabled the team to track the birds throughout their territories, ultimately collecting over 1000 GPS points that will allow them to study how these birds are utilizing their territories. Additionally, the team collected over 100 hours of behavioral data, documented foraging success, and recorded over 40 roosting events, the latter already yielding interesting results. “Statistical analyses are still underway, but our preliminary findings suggest that kestrels in the area heavily rely on human structures for overnight roosting,” Brooke notes.

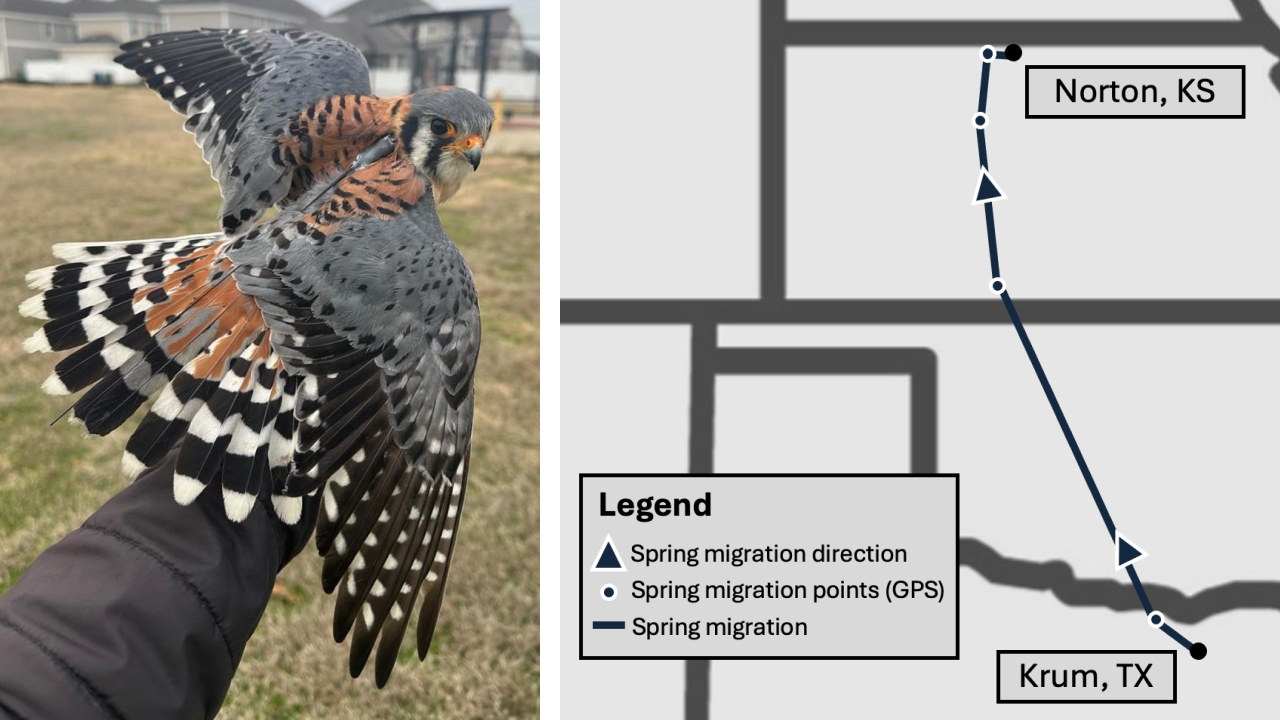

While the radio transmitters allowed the team to record precise locations on the wintering grounds, another technology is allowing the same precision from afar. “This year, we fitted three kestrels with global system for mobile (GSM) trackers, which use satellites and cell towers to communicate accurate remote locations,” explains Dr. Jim Bednarz, the project’s principal investigator. “One such kestrel has already completed a 450+ mile migration to the area of Norton, Kansas, where we assume she will nest this late spring and early summer.” (Her migration path so far is seen at right above.) In total, the UNT team has now precisely documented the full annual cycle of eight American Kestrels—some of the first such precise migration tracks ever recorded for the species.

“Kestrels are still common in North America, but the population has been mysteriously declining for at least five decades,” laments Jim. “It’s important that we figure out when and where they’re most at threat now, so we can reverse these declines before the situation gets more serious. The wintering stage of the American Kestrel life cycle could be critical to understanding the overall population viability of this species.”