Pat Burnham

On March 12, the republic’s 30th anniversary, Mauritius wildlife advocates want to “become famous for preventing wildlife extinctions, not just for historical wildlife extinctions”

Once the world’s rarest bird of prey, the Mauritius Kestrel will take its place as the national bird of the Republic of Mauritius on March 12, 2022, the country’s 30th anniversary as a republic and 54th as an independent nation. Mauritius was once home to the flightless dodo, a huge pigeon relative and perhaps the world’s most well-known icon of human-driven wildlife extinctions. The Mauritius Kestrel, by contrast, is a bird conservation success story in progress, having recovered from a low of just four known wild individuals in 1974 to about 350 wild falcons today.

“Mauritius will become famous for preventing wildlife extinctions, not just for historical wildlife extinctions,” said Vikash Tatayah, conservation director for the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation, which leads conservation efforts in Mauritius and called for the kestrel’s designation as national bird. “The Mauritius Kestrel is a symbol of our republic, and it is a symbol of optimism and cooperation. Our work to save this species, and many others in our beautiful land, is not yet done, but we know it is possible to do. We are grateful for the partnership of the Government of Mauritius and all of our allies at home and abroad who helped make this day possible.”

The Mauritius Kestrel will have a role in the republic’s 30th anniversary celebrations, with remarks from Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth in his national address, a commemorative postage stamp and first day cover, and a one-hour Mauritius Kestrel documentary from the Mauritius Broadcasting Corporation, the national television network.

The Mauritius Kestrel is a forest-dwelling falcon that evolved to feed primarily on brightly colored Mauritian day-geckos, which it plucks from trees. It may also catch other lizards, small birds and introduced small mammals. Less than 1.5% percent of Mauritius’ native forest remains relatively intact, and the kestrel is further threatened by invasive predators and the loss of suitable nesting cavities. After a post-recovery peak of approximately 600 birds in the mid-2000s, falcon numbers have declined again to about 350, but conservationists are confident that the trend can be reversed.

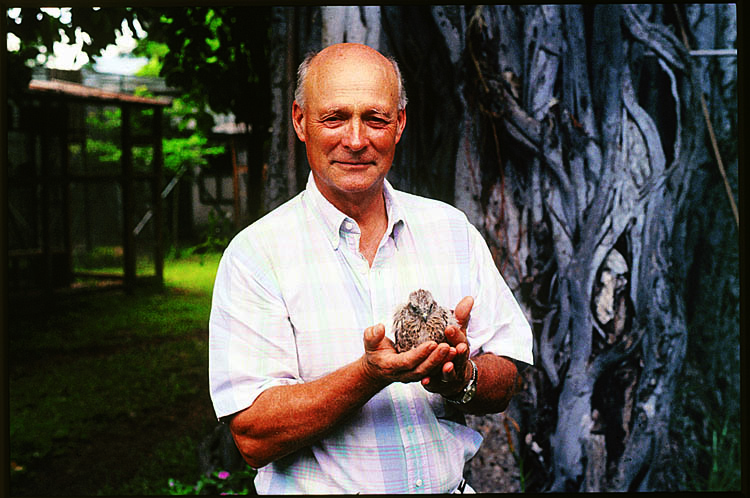

“The work on the Mauritius Kestrel, because of the loss of habitat and introduced species, will have to be carefully managed for the foreseeable future. By declaring the Mauritius Kestrel as the national bird, the Government of Mauritius is recognizing its value and making a commitment to care for it and the other wildlife of Mauritius.” said Carl G. Jones, Scientific Director, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation, Chief Scientist, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, and Indianapolis Prize-winner, who started working with the Mauritius Kestrel in the late 1970s and is credited as the individual who refused to give up on the species in its darkest days, against the advice of some experts. “The greatest joy has been to see the development of local capacity and the work that was once largely done by expatriate ornithologists is now being conducted by a growing group of young Mauritians.”

By the 1970s, only four Mauritius Kestrels remained alive. Habitat destruction, invasive species, and DDT had taken their toll on the unique forest-dwelling bird. Responding to concerns raised by Mauritian citizens, international conservation organizations including the International Council for Bird Preservation (now BirdLife International), Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and The Peregrine Fund sent staff and resources to see what could be done. A pioneering captive breeding program and numerous other interventions began to turn the tide. Today, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation and the Mauritian government lead the efforts, supported by international partners. The Mauritian Wildlife Foundation has saved five bird, three reptile and one bat species from the brink of extinction.

“At the beginning of the project when I studied the last wild birds, I found that they were naturally tame and curious and soon got to know them individually,” said Jones. “During one tropical downpour I sheltered under a cliff overhang, and the kestrel I had been watching joined me and perched on a rocky ledge just a meter away. As a result of such intimacy, I gained great insights into their lives, and we were able to build a picture of how the kestrel lived and to understand its needs so we could start to build the conservation programme for it.”

“We must act now to turn around Earth’s great biodiversity crisis, and the Mauritius Kestrel shows that we can do it,” said Patricia Zurita, CEO of BirdLife International, a partnership of more than 115 national conservation organizations worldwide, including Mauritian Wildlife Foundation. “This is the moment to conserve and restore Earth’s Key Biodiversity Areas—like the forests of Mauritius—for the benefit of humanity and wildlife alike. Congratulations and deep thanks to the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation, the Government of Mauritius, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, The Peregrine Fund, and all those who have brought us here today.”

“The recovery of the Mauritius Kestrel was our first international program,” said Chris Parish, president and CEO of The Peregrine Fund. “The success of the program encouraged us to expand our work to more than 65 countries. We hope that naming the Mauritius Kestrel as the national bird of Mauritius will inspire people around the world to participate in conservation and understand that, when we work together, we can save species.”

“The success story of the Mauritian Kestrel restoration is proof of the power of collaboration and of BirdLife International’s approach to delivering meaningful impact by bringing together scientists, partners and national champions,” said Nathalie Boulle, a member of the BirdLife International Advisory Group. “These outcomes are often hard fought, they require patience, skill and teamwork but that is what BirdLife is all about. I consider it a privilege to sit on the International Advisory Group and, as a Mauritian, I am delighted along with many others to have supported the kestrel project.”