Alan Clampitt

BOISE, ID – Biologists from The Peregrine Fund successfully trapped and tagged California Condor number 1,000 marking yet another milestone in this special bird’s life and the conservation effort to bring this species back from the brink of extinction. This condor represents the 1,000th condor hatched since the recovery program began. The population now numbers more than 500 with over half of those flying free in the wild. The Peregrine Fund is a member of The Southwest Condor Working Group that includes state wildlife agencies of Utah and Arizona, federal partners including Zion National Park, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, and National Forest Service.

California Condor number 1,000 hatched last May (2019) in Zion National Park and was the park’s first condor nestling to fledge successfully on September 25, 2019. The young condor arrived at the trapping location in northern Arizona at Vermilion Cliffs National Monument late in the evening this past Wednesday, May 20. Peregrine Fund biologist, Angela Woodside, quickly identified the bird and began to craft a plan to trap the juvenile condor the next day. She noted that Condor 1K, as it is now being called, was alone making this trip to the trap site without the help of its parents.

This historic accomplishment marks a significant moment in California Condor recovery efforts. Not only is this the first condor in recorded history to fledge from Zion National Park, but it has survived for an entire year, is behaving increasingly independently, and appears to be in strong health. It also reminds us that it is important to celebrate conservation successes!

Chris Parish, Director of Global Conservation and longtime California Condor biologist for The Peregrine Fund, was excited to hear the news about Condor 1K. He states, “In science and conservation we spend a lot of time quantifying things with numbers and years, but this number is truly exceptional. We were down to only 22 individual California Condors just a few decades ago, and today we are witnessing the 1,000th condor thriving in a landscape shared with humans. It’s important for us to celebrate this. We don’t always take enough time to celebrate successes, but this is pretty phenomenal!”

In 1982, only 22 California Condors were left in the world. Due to the steep decline of the population, the remaining wild condors were captured and held in captivity for safekeeping, which gave rise to a tremendously successful captive breeding program that has allowed for reintroduction of the endangered birds back to the wild beginning first in 1992 in California and following in 1996 in Arizona. Lead poisoning is the primary cause of condor mortality and a remaining obstacle to the recovery of the population. Hunters and others are helping to reduce the amount of lead in the environment, improving chances for condor survival.

Trapping Condor 1K was a bit nerve-wracking. Woodside recalls, “I didn’t want to risk missing the opportunity to trap 1K, so I hiked to the rim of the cliffs before sunrise. Condors tend to be late risers, but with first light around four a.m. these days, there were already birds—mostly the dominant adults—feeding in the baited trap when I arrived. Unfortunately, I saw no sign of 1K, so I snuck down into the trap blind to wait. A little before nine a.m., I got my first glimpse of 1K strolling across the top of the trap and hopping down to the ground next to it. 1K disappeared from my view for a bit, and I waited some more, tensed, ready to drop the trap doors as soon as I got my chance. Finally, at just before 9:15, I was able to close the door and relief flooded me.”

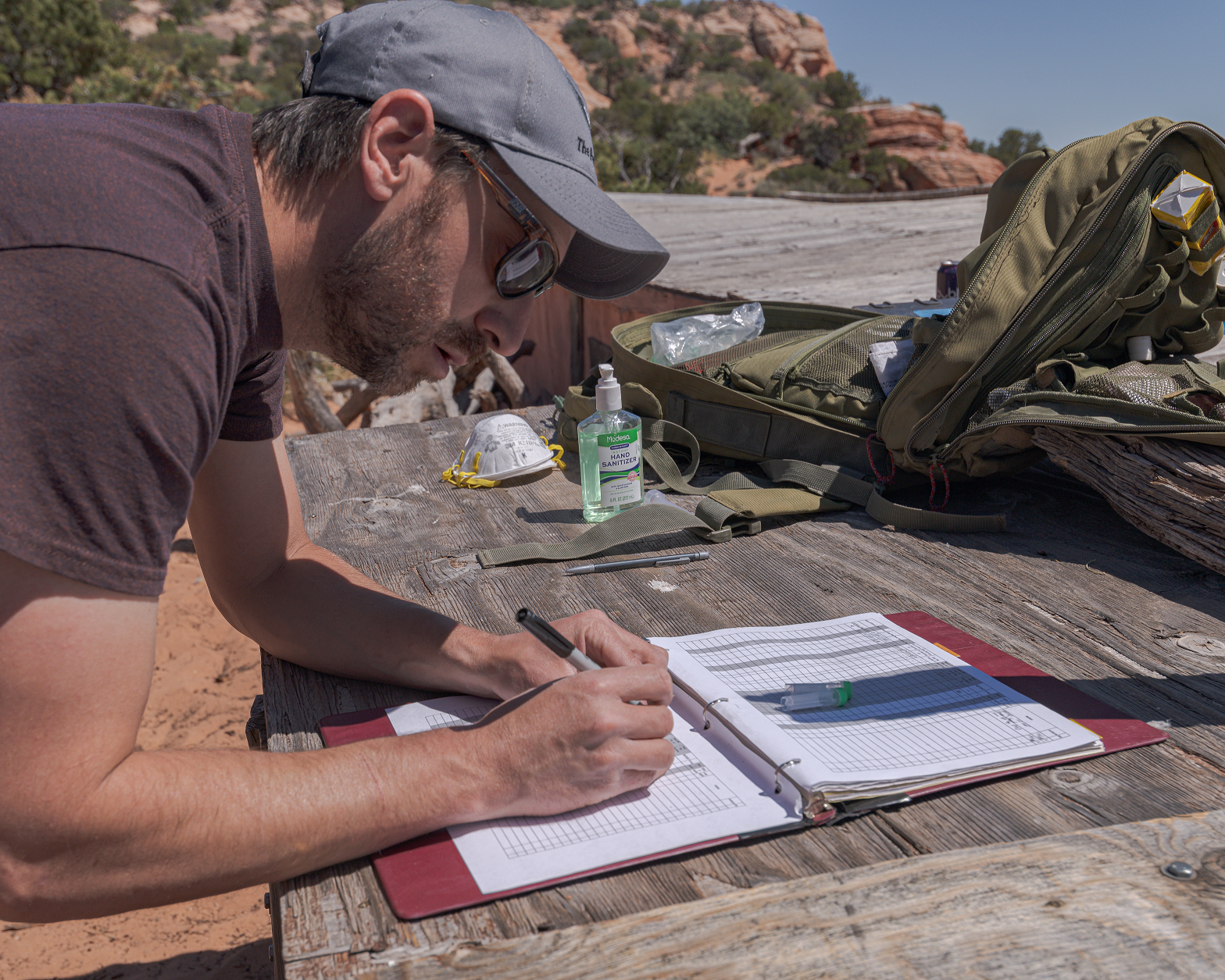

Woodside immediately called Condor Program Manager, Tim Hauck, with the good news and Hauck jumped in his truck to head to the trapping site. Once there Woodside and Hauck readied the equipment needed to tag, transmitter, and provide health tests for the bird. Hauck recalls, “I was pleased that we only had to have the bird in hand for about five minutes to do everything we needed. This greatly minimized any stress to the bird. We took a weight, drew blood for analysis, administered vaccinations, and attached a transmitter and a freshly-painted vinyl tag sporting the number “1K” to the wing using a method much like, and as painless as, ear-piercing for a human.”

The transmitter will help biologists better understand condor movements and foraging behavior. Because there are so few of these birds in the wild, it remains important to monitor them on an individual basis in case a bird experiences a health problem like lead poisoning. Hauck continues, “That being said, there are some birds we haven’t laid eyes on in years, but we know they’re surviving because of the transmitter data. This is important. We know that there are birds out there surviving without coming to our feeding stations or having regular checkups. This gives us confidence for the future survival of these birds in the wild without requiring intensive management.”

The quick health check by Hauck and Woodside showed that Condor 1K is a healthy 17.3 lbs, was well hydrated, and has developed good muscle mass. They won’t know yet whether the bird is male or female until the blood analysis comes back from the lab.

Back at Zion National Park, the staff have conflicting emotions. Janice Stroud-Settles, Wildlife Program Manager, says, “Condor 1K’s capture is a bittersweet moment for the dedicated team of biologists and volunteers at Zion National Park. We are ecstatic that 1K is maturing, expanding its range, and becoming increasingly independent of its parents, but at the same time we are starting to experience an “empty nest” feeling after a year of intense monitoring.”

In fact, Hauck tells us that, “This past Saturday, two days after being tagged, Zion National Park biologists spotted Condor 1K along with its parents. We were happy to hear this news and were not surprised 1K went back to that area, because just outside of the park, there is ample opportunity to find food. Ranchers in the area move their livestock seasonally, and some animals die of natural causes. These animals provide a great food source for scavengers like California Condors and the birds play a crucial role in helping to dispose of the rotting carcasses.”

For now, Woodside is just happy that Condor 1K is doing well. She recounts, “Being the first human to put hands on this condor was not a responsibility I took lightly, and I felt an enormous sense of pride and accomplishment seeing the young condor take to the air again, unhampered by the new tags and transmitter, unfurling those shockingly huge wings and catching the uplift at the cliff’s edge.”

For more information on the California condor recovery program, visit:

http://www.peregrinefund.org/projects/california-condor